Could You Destroy a Data Center?

30 Jul , 2021

Terrorist Threat Against a Data Center

Seth Aaron Pendley left the January 6th riot on Capitol Hill with an idea. An idea for a novel, characteristically 21st century kind of terrorist attack.

The 28-year-old Texan began sharing his ideas on a right-wing extremist website called “MyMilitia.com.” Writing under the screen name “Dionysus,” he explained that he was going to “conduct a little experiment”–a “dangerous” one that would “draw a lot of heat.”

Another member of the forum asked what he was getting at.

“Death,” Pendley replied.

(image via 92.1 Hank FM)

Later that month, Pendley began collaborating with another individual via the Signal app. In encrypted text messages, he disclosed the plan:

He was going to blow up a data center.

Pendley was already gathering intel. He put together a list of potential targets, and sent it to his partner the following month.

The partner offered to help him obtain C4 explosives.

Pendley replied. “Fuck yeah.”

Then Pendley sent his contact a hand-drawn map of one facility in particular: the Amazon Web Services center at Smith Switch Road in Ashburn, Virginia (about 35 miles northwest of Washington D.C.). A giant, monochrome, three-warehouse facility best known for catching fire in 2015. Drawn onto the map were indications of where he would enter and exit the premises. He also mentioned that he was going to paint his car, and switch its license plate, to avoid identification by law enforcement.

In March, the plot ramped up. Pendley’s partner arranged a meeting with an explosives supplier for the 31st. Pendley explained to the supplier why he was doing what he was doing:

“The main objective is to f*** up the Amazon servers,” he said, because they were the ones servicing the FBI, CIA, and other government agencies. “The oligarchy” would be angered, causing them to overreact in retaliation. Their overreaction would, in turn, alert the American people to how they were living in an unjust “dictatorship,” and inspire them to rise up. “[S]ome of the people that are on the fence [will] jump off the fence.”

On April 8th, Pendley met again with the supplier. The supplier handed over the goods, and demonstrated how to arm and detonate them. Pendley stuffed the delivery into his car, and got ready to blow up a data center.

Is it Even Possible To Breach a Data Center?

Was it even possible?

Data centers are some of the most highly guarded places in the world. It’s easier to breach the office of the Speaker of the House than the server rooms of an Amazon or Microsoft DC. Still, there’s no such thing as perfect security.

Early this year, I interviewed a man who goes by the name “Freaky Clown” (or FC, for short). FC’s a security expert, whose specialty is breaking into buildings. In a good way. Major government institutions, banks, and large corporations hire his firm, Cygenta, to conduct penetration tests against their physical and cyber security infrastructure. That might mean showing up to their headquarters in a disguise, then sneaking into the server room with a USB, or finding a way up to the CEO’s office to rifle through their personal documents.

Among his many good stories, FC told me about a time when he broke into the data center of one of the world’s major financial institutions:

[S]o this bank decided to be more secure by having their own building filled up with their computers worth billions and billions of pounds going through their system. And what they do was they decided the best way to secure this place is to have guards on it. No, not armed guards. I’m not going to say they were armed, but they had guards. And these guards were ex-Gurkhas. because we know that if you get in, all damage is done.

Now, Gurkhas are a ferocious, amazing, well-trained group of soldiers, right? And now these ex-Gurkhas had got work as a security firm and they had got the contract for protecting this one building. And so we were asked, like, “Can we get into this building?” This is one of the few times where it’s like, can you even think about getting in? All right,

So I’d go and look at the building and I’m doing a lot of recon with it and I noticed that there’s a couple of things where they do like a shift change and stuff up. And during the shift change, what they do is they have the new shift come in and the old shift, the new and the old shift both go into the building to do the hand-off and one guy is left outside. All right, so just one guard to take care of. And this only has about like a 10, 15-minute window.

And so I hired a car. I sat outside this data center in a somewhat known suspicious area and I waited for the last of the new squad to turn up. And as the gate is shutting, I floor my car – oh, a hired car rather speeds through the barrier, smashed the wind mirror off, go through a hedge over some curves, grabbed the guard who’s been left outside, shove him into the car, handbrake, turn around and sort of skid around the car park a little bit and then back out through the barriers to a safe location where I can explain to the guard why he’s just been kidnapped.

I asked him how none of the other guards managed to react to his loud, obvious break-in.

[W]e’ve got half the fence so far away from, like, the data center in case, like, people throw stuff. Which, you know, to be fair, it has happened before. But if it’s far enough away, then no one notices because, well, all of the guards have just gone into the building. So no one really cares about it. And the response time of people seeing that happening and then figuring out what to do and then get out to stop it doesn’t really matter. It’s already done. It’s happened. Things happen really fast and people aren’t always as good as they imagine they would be in these situations.

Unlike Seth Aaron Pendley, FC is a trained professional with years of experience breaking into secure sites. But like Pendley, he’s just one man. What if a nation state were to use an expert team of agents to pull off a more sophisticated attack? What if they planned for months or years in advance, and cultivated insiders? There’s no amount of security that could eliminate all possible scenarios.

What Would Happen if You Destroyed a Data Center?

Seth Aaron Pendley hoped that, through terrorism, he could “kill off about 70% of the internet.” Was that within his power?

In practice, even the worst, most comprehensive destruction of a major data center wouldn’t cause any significant, lasting impact to the entire internet. In fact, only the cloud provider and their insurers would be on the hook (to say nothing of the risk to on-site employees). There are a number of basic reasons why this is so:

- Only half of the world’s enterprise data is stored on the cloud.

- These days, Amazon controls only a third of the total market in cloud services.

- Amazon has data centers all over the world, 38 in northern Virginia alone.

Most important of all: the cloud is a network. When one node goes down, other nodes are designed to pick up the slack. Data is easily replicated across sites, and traffic easily rerouted, so even the destruction of a very large facility would cause no permanent damage to users.

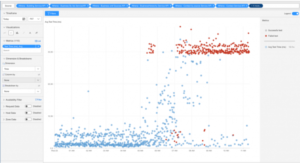

To understand how this works, we can look at what happened last fall at AWS’ US-East-1 (also in northern Virginia). An incident particularly pronounced, particularly well known, because it occurred on the eve of the internet’s busiest weekend of the year, Black Friday.

Beginning around 8:15 AM EST on Wednesday, November 25th, US-East-1 experienced “severely impacted” performance. By 10:00 AM, it was a full-on outage.

The root cause was with the API for Kinesis Data Streams, a real-time data streaming service. From there, a chain reaction affected multiple other AWS services down the line. The effect of the failure was so widespread in the system that, ironically, it even impacted Amazon’s ability to post updates to their Service Health Dashboard–the place where people go to check up on the status of AWS when it’s experiencing issues.

(image via Catchpoint)

The incident demonstrated just how many people rely on US-East-1. Its failure caused companies like Adobe, Roku, Coinbase, Flickr, 1Password, Glassdoor, GameStop and many, many more to experience minor outages or slow loading times on their websites. And, as pointed out in The Register:

Problems could well have been exacerbated by the fact that AWS defaults to US-EAST-1 when endpoints are used with no Region set. US-EAST-1 is, according to the company’s documentation, “the default Region for API calls.”

All of AWS us-east-1 is down pic.twitter.com/SdO5J7qoEg

— Kemal Ahmed (@carpetfortwo) November 25, 2020

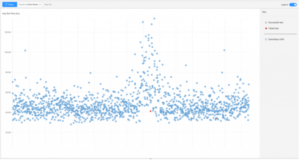

But there’s another side to this story. US-East-1 was down for hours–it was fixed later that day–but end users tended to experience significant performance issues for only short periods of time. Maybe 15 or 30 minutes in the morning, before things returned to normal. Here, for example, is how GameStop’s day looked:

(image via Catchpoint)

What happened was that, shortly after the outage kicked in, AWS began rerouting all of the traffic from US-East-1 to other DCs. They didn’t have to go very far, either, as there were 37 other data centers in the region to tap into.

What we’re left with is a juxtaposition. US-East-1 is one of the biggest, most important DCs in the world, with massive traffic flowing through every day, in particular during the week of Black Friday. An error with an API kicked off performance issues for a whole swath of the North American economy, yet its effects were relatively minor and very brief due to the efficiency of AWS’ content delivery network. A giant impact, short-lived.

Bottom Line: The Cloud is Sensitive

Most people don’t understand what the cloud is (partly by design). We think of it as some ethereal, omnipresent thing floating out in space, storing our data in some way or another.

In reality, the cloud has physically concentrated the world’s data more so than ever before in history. Centralized data centers process and store giant globs of information, all from specific locations you can point to on a map. That makes them big, fat targets for potential nation-state spies, and terrorists.

That’s why Amazon, its employees, and the United States got lucky when, on January 8th, 2021, a concerned citizen contacted the FBI. They reported visiting MyMilitia.com, where they witnessed a series of alarming statements from another user on the forum.

The user, Dionysus, used an email address registered to one Seth Aaron Pendley. Pendley had just recently bragged on Facebook about taking part in the terrorist attack on the U.S. Capitol. His statements on the forum represented a pattern.

The authorities planted a source to lure Pendley into a partnership. The source worked with Pendley on planning the attack, then connected him with a purported explosives dealer–in reality, an undercover agent. Pendley met with the “dealer” on April 8th, and received a delivery of chemically inactive explosive devices.

After the hand-off, agents monitoring the deal closed in and completed the arrest. In a search of his home in Wichita Falls, Texas, “they found an AR-15 receiver with a sawed-off barrel, a pistol painted to look like a toy gun, masks, wigs, and notes and flashcards related to the planned attack.”

On June 9th, Pendley pleaded guilty to “malicious attempt to destroy a building with an explosive.” His sentencing is scheduled for October 1st. He faces 5 to 20 years in federal prison.